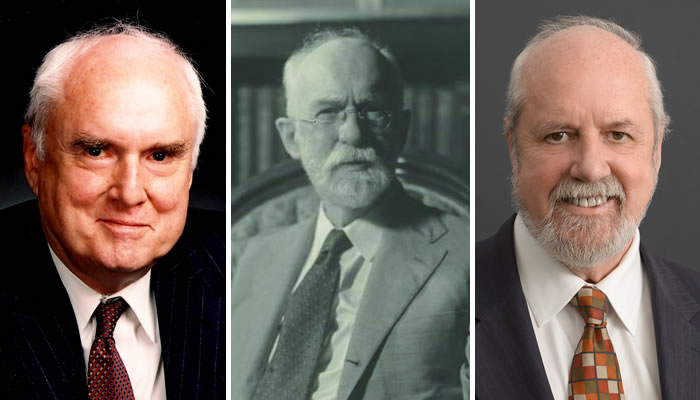

When Forest Preserves founding father and prominent architect Dwight Perkins passed away in 1941, his grandson Dwight H. Perkins II, was only seven. Dwight’s brother, L. Bradford Perkins, wasn’t born. (They also had two sisters, one of whom is still alive.) Yet growing up in the Perkins family, the brothers always had a strong sense of their grandfather’s legacy. We spoke with them in the week leading up to the Forest Preserves’ 100th anniversary board meeting.

Did you know your grandfather personally? What time did you get to spend with him?

DHP II: He was the grandfather whose beard I pulled. My grandfather and grandmother only lived a block away. Most of what I know about him is what I’ve been told by my father and my aunt.

LBP: I was born two years after Grandpa died. But as my father had, I followed in his professional footsteps.

What do you remember about your grandfather, either directly or through your family? What kind of person was he?

DHP II: The thing that I always knew about from the beginning, I knew the forest preserves clearly, and I knew about the National Historic Landmarks he designed. The thing that gets the most attention from architectural historians was the fact that he was a core part of the Prairie School of architecture. There was a substantial period when they all shared offices in Chicago: Frank Lloyd Wright, Marion Mahony Griffin, Walter Burley Griffin and others.

He was poor when he was young. His father died when he was around ten. He never had a high school degree, but he passed exams to get into MIT in architecture. Then he was part of a liberal reform group, partly his Unitarian church and the circle around that. When he was young, he worked with Daniel Burnham.

But the thing that has always struck me was his integrity. He was made schoolboard architect when it had a majority of reformers on it, but then the crooks got control. They asked him to resign, but he refused. His appointment was one where they could not just fire him. He said to them that they had to try him.

That trial became a huge public thing. Our family has cartoons—the Chicago Tribune had a color political cartoon on the front page every day. The cartoon had my grandfather as a shining white knight standing before the school committee, who all had bottles of whiskey and beer. The real issue was that two members of the schoolboard wanted him to source their materials to their associates and he refused. He was working to make everything competitive.

They did eventually fire him for insubordination, but the best architects in America testified on his behalf. His reputation was made nationally. He never had any trouble getting work after that.

Arguments over the forest preserves in those days were very much arguments between developers and those who wanted to preserve the land. The fight over the forest preserves went on for a long time, between those trying to use land to make money and those who were trying to preserve an ecological border around the city for the good of the population. That’s the way it was always taught to me.

LBP: To start out with, I grew up in a house that he had designed and built. To grow up in a landmark Prairie School house, as someone who would become an architect, that has a significant impact as you’re growing up. The gardens of that house were done by Jens Jensen. It was native planting, built around a small pond in the back, which had goldfish. They were quite lovely gardens, on larger grounds than your typical lot in Evanston.

My aunt Eleanor was the family historian. My wedding present from my aunt was a biography of Grandpa. I knew most of the stories in that draft biography. And there’s a large section devoted to efforts to create the forest preserves. One small segment of the preserves was on the parcel next to where I went to school in Evanston. It’s now called Dwight Perkins Woods.

Did you ever get a sense of how he viewed Jensen and other forest preserve collaborators?

DHP II: Because Jensen was a landscape architect, they’d known each other and been associated for some time, but the group was broader than just the two of them. It’s hard to imagine, but Chicago at that time was a much smaller place. There were groups of people associated with each other who were very much a part of thinking about where Chicago should go and what it should be, and every now and then having some influence over how it actually came into place.

LBP: I always grew up knowing Jens Jensen was one of his important friends and collaborators. There was a particularly close relationship between Grandpa and Jensen. Not only did they work on the original report together, in the years that followed they were lobbying legislators, leading walks and tours. They both were actively involved in that effort.

As my brother said, back at that time, in 1904, the civic leadership group was much smaller. On my wall at home I have letters from Jane Addams, Daniel Burnham and others. They all knew each other.

Perkins and Jensen were influential across many spheres. How do you think they managed to do so much within their lifetimes?

DHP II: When you’re in the early stages of building something like the City of Chicago, the people who are at a level to think about these broader issues know all the people who are influential, and it’s not that big a group. You can do a lot in the early stages of a city or other organization.

I work in Asia in development, and I’ve found you can make huge changes in the early stages, in ways that you can’t once something’s well established. Chicago was a booming city, gone from hardly anything to one of the major cities in the country in 50 to 60 years. My grandfather was around at a very influential time.

LBP: I think it was a particular moment in time. You can attribute a lot to Burnham’s influence, and the great impact of the Columbian Exposition in terms of galvanizing the quality of the city environment.

It wasn’t just the City Beautiful movement, but an overall interest in planning and design that took hold in Chicago, first with Sullivan and Burnham, in the first generations, but then with Wright, Elmslie, Purcell and others.

There was a belief that you could make it better for the city through design. These were great ideals that captured people’s imagination. In a city growing rapidly, it seems to have caught hold.

How has Perkins’ legacy influenced your own appreciation of nature?

DHP II: It’s hard to say how much my grandfather had to do directly with my appreciation of nature, but the forest preserves were very much part of my life growing up.

As a child, I went to the preserves often. In 7th and 8th grade, we’d go camping. We just went out into the woods somewhere; I don’t even think we had a tent. Sometimes we would sneak into a nearby drive-in. In those days, the 1940s, no one, including my mother, thought twice about letting a group of 13-year-olds camp by themselves.

LBP: I was brought up to understand how important nature was. In addition to being an architect, I’m also a planner, and some of the ideas that were behind the plan that includes the forest preserves is built into some of the planning I do.

I just finished two and a half years as chief planner for the city of Hanoi. Part of the plan that is now law in Vietnam is the greenbelt around the capital, which they refer to as a green corridor. It basically preserves all natural areas in a huge swath—over 2,000 square kilometers of farmland and natural areas. It forms a complete ring around the capital.

When I presented to the prime minister and the rest of the leadership, I used examples from all the leading cities worldwide, including the forest preserves around Chicago. It was a concept that the minister embraced from the beginning.

How do you think he would rank the Forest Preserves among all his other great life achievements?

DHP II: In terms of his civic accomplishments, the forest preserves is clearly the dominant one. Professionally, it would be the whole collection of his architectural work, his Prairie School work, the school buildings, Carl Schurz and lots and lots of others. He had a big practice, with schools at center of it.

His interest in the environment and being out in the open, undeveloped lands was something that was close to him all his life.

LBP: I appreciate the influence he had in modernizing school planning and design, which, through my father’s firm, led to Crow Island School, then the thousands of schools that followed it. I feel the importance of that part. But the forest preserves and the parks have to be the high point of his career.

The goals of the Forest Preserves’ Next Century Conservation Plan includes expanding our holdings and restoring 30,000 acres of land in the next 25 years. What are your thoughts about the Forest Preserves’ current efforts to sustain the preserves, and your grandfather’s legacy?

DHP II: I am sure that my grandfather would be very pleased with the efforts to expand the preserves and to restore many of the existing acres. I don’t believe he felt that his specific ideas and plans for them should be written in stone, and the direction in which they are evolving seems to me to be very positive.

The fact that many of those involved in being stewards of the preserves are volunteers would particularly appeal to him. He himself and his various collaborators were themselves volunteers. I don’t believe he himself was ever paid a cent for his involvement.

As for your effort to remember those including my grandfather who played a role in getting the whole enterprise underway, I could not be more pleased, and I am absolutely certain that my father would feel even more strongly that way if he were alive today.

LBP: I’ve been very encouraged to see they’ve continued the acquisitions of land. Early on, there were all these efforts to encroach, and they were always battling back. There were times when large portions may have been under threat. That seems to be over, the legacy has been protected, so it’s nice to see it’s continuing to evolve and expand. All of us are very proud of what he and others accomplished.

Dwight H. Perkins II is an economics consultant who advises Asian countries transitioning from a planned to a market economy. He is a professor of economics, emeritus, at Harvard University, where he has served on the faculty since 1963, including as economics chair.

Bradford Perkins is an architect and planner, and the founder and chairman of an international architectural and planning firm, Perkins Eastman Architects.